Although many Americans are lining up for their COVID-19 vaccine, we’re still far from herd immunity. But experts are hopeful that more Americans will start to resume medical care services. Health economist Jane Sarasohn-Kahn explores how many Americans have put off much needed healthcare during the pandemic—and its lasting effects.

By Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Although we’re all hoping to see the COVID-19 pandemic come to an end, public health prognosticators expect the pandemic to continue well into the summer. The promise of herd immunity through vaccinations feels so close, but, in reality, it’s still a far-off goal.

The development of a COVID-19 vaccine was turbocharged, with life-science companies doing their level best to deliver several effective candidates to prevent the spread and lessen the fatal impact of the coronavirus on human life. However, the concept of “warp speed” cannot be applied to the vaccination administration process.

“The prospect of a vaccine offers hope for 2021, but that solution will not come soon enough to avoid catastrophic increases in COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths,” warns an opinion article published in a December 2020 issue of JAMA.

Vaccines on the supply side don’t equal vaccinations on the patient-demand side—the proverbial “shots in arms.”

But communities and states are trying their best efforts to get more Americans vaccinated, according to Jeff Zients, the White House’s coronavirus response coordinator.

“We’re mobilizing teams to get shots in arms,” Zients said in a February 24, 2021, briefing. “We continue creating more places where Americans can get vaccinated,” he continued. “We’ve now expanded financial support to bolster community vaccination centers nationwide, with over $3.6 billion in FEMA funding to 44 states, tribes and territories for vaccination efforts. We’re bringing vaccinations to places communities know and trust: community centers, high school gyms, churches, and stadiums nationwide.”

A Return to Normal Utilization of Medical Care

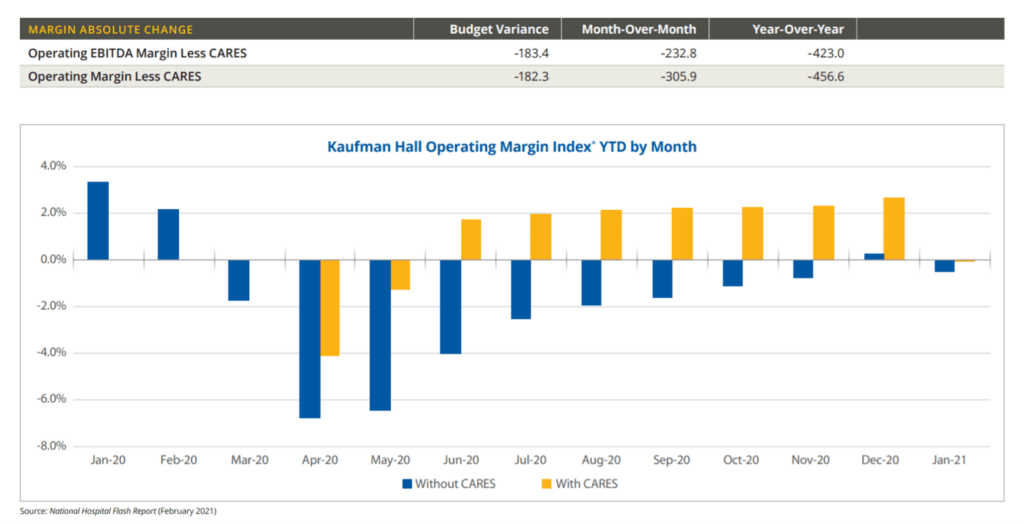

Many Americans have attempted to manage their risk of exposure to COVID-19 by avoiding visiting the doctor or hospital and not receiving medical care. But that self-rationing and care avoidance has hit healthcare providers hard, according to the latest National Hospital Flash Report from Kaufman Hall.

“Hospitals and health systems had a difficult start to 2021 as declining volumes, falling outpatient revenues and rising expenses contributed to significant January margin declines,” the report observes.

With the advent of vaccinations, U.S. hospitals are hopeful that they can recover normal utilization, but they will still face what Kaufman Hall foresees as “a long road to recovery.” The January 2021 decline in hospital financial metrics underpinned Kaufman Hall’s less-than-optimistic forecast on American hospital financial health, asserting that the pandemic’s repercussions for healthcare will persist, in their words, “indefinitely.”

With the advent of vaccinations, U.S. hospitals are hopeful that they can recover normal utilization, but they will still face what Kaufman Hall foresees as “a long road to recovery.” The January 2021 decline in hospital financial metrics underpinned Kaufman Hall’s less-than-optimistic forecast on American hospital financial health, asserting that the pandemic’s repercussions for healthcare will persist, in their words, “indefinitely.”

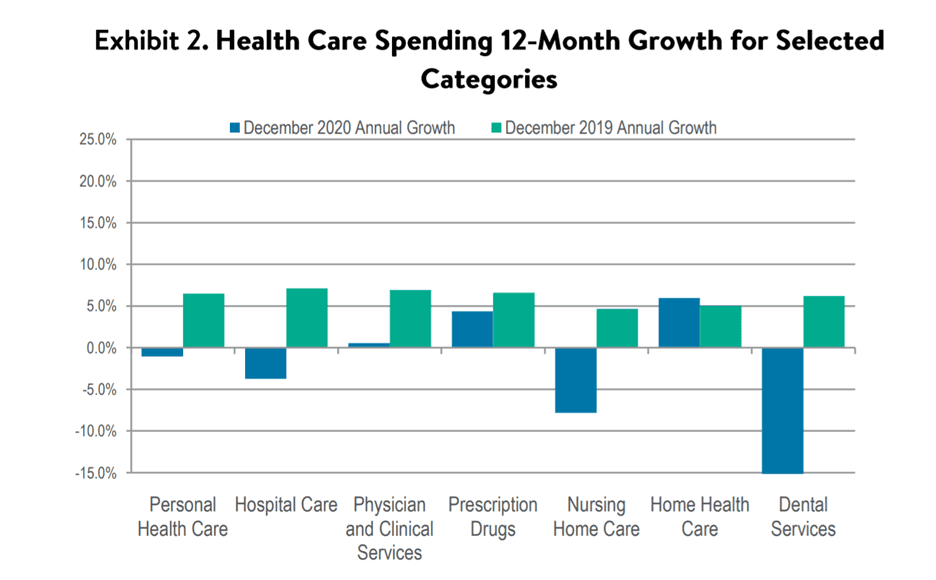

Another take on healthcare finances comes out of the latest report on health sector spending from the Altarum Institute showing data from December 2019 to December 2020. As you gaze across the bar chart, note the blue bars which represent annual growth (or decline) in December 2020. The largest declines were seen for dental services, nursing home care and hospital care. You can see the increase in spending for home healthcare and prescription drugs for 2020 annual growth.

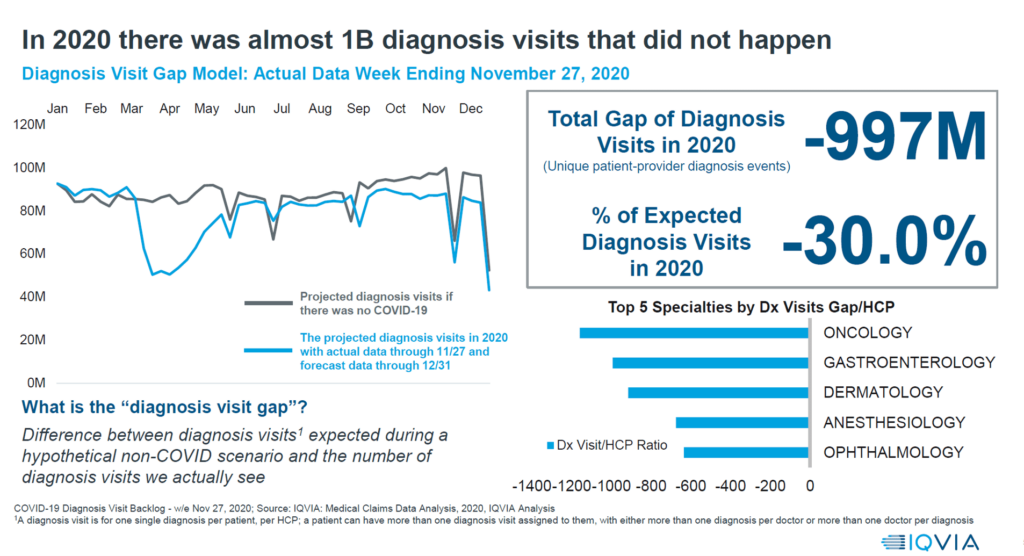

A shockingly large number of missed diagnosis visits—nearly 1 billion—was a topline finding in a recent IQVIA study on how COVID-19 has impacted healthcare in the U.S. The most prevalent specialties hit by this diagnosis visit gap were oncology (delayed cancer screenings), gastroenterology (postponed colonoscopies) and ophthalmology (eye exams).

A shockingly large number of missed diagnosis visits—nearly 1 billion—was a topline finding in a recent IQVIA study on how COVID-19 has impacted healthcare in the U.S. The most prevalent specialties hit by this diagnosis visit gap were oncology (delayed cancer screenings), gastroenterology (postponed colonoscopies) and ophthalmology (eye exams).

Together, the Kaufman Hall, Altarum Institute and IQVIA data paint a concerning forecast for U.S. healthcare providers. But turned on its head, the picture also features health citizens in the U.S. who missed the healthcare encounter. The outlook for them is also difficult based on the fact that so many patients avoided care in 2020, and many have continued to delay care in the first weeks of 2021.

Together, the Kaufman Hall, Altarum Institute and IQVIA data paint a concerning forecast for U.S. healthcare providers. But turned on its head, the picture also features health citizens in the U.S. who missed the healthcare encounter. The outlook for them is also difficult based on the fact that so many patients avoided care in 2020, and many have continued to delay care in the first weeks of 2021.

The ‘Shadow Health Crisis’

This care-avoidance will translate into thousands dying in 2021—not from complications due to COVID-19, but for other reasons not otherwise expected to result in death.

Bloomberg recently referred to patients avoiding care as the pandemic’s “shadow health crisis.”

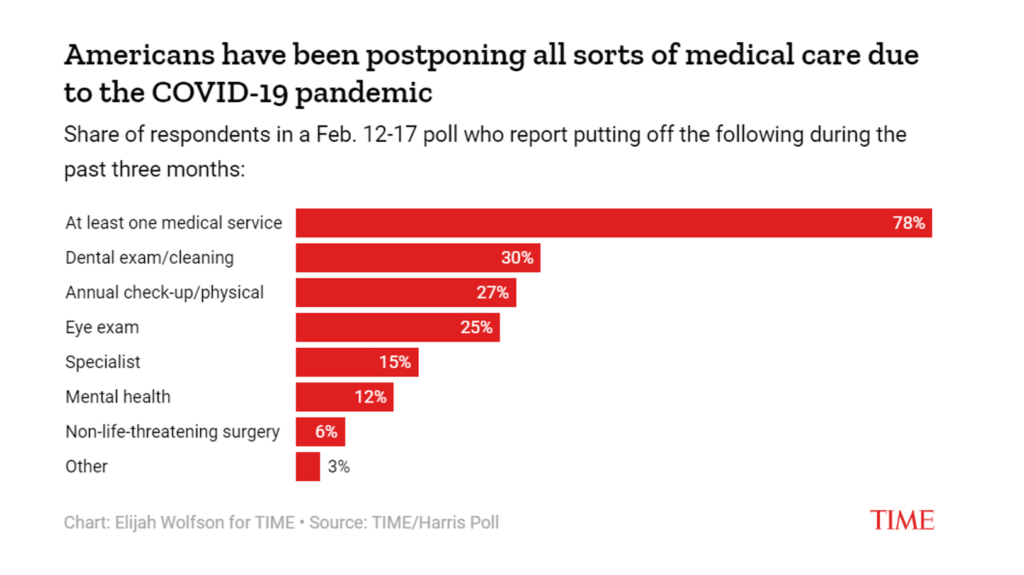

A TIME-Harris poll conducted in mid-February found that nearly eight in ten people in the U.S. had put off some form of medical care, spanning dental exams, annual check-ups, eye exams, seeing specialists and mental health care.

While the percent of people not seeking specialty care at 15% might seem relatively small, these specialists include cardiologists and oncologists, among others. As heart disease has been the No. 1 killer of Americans year-upon-year—until 2020 when COVID-19 emerged as the top cause of death in the U.S.—delayed heart care can result in cardiac emergencies, morbidity and ultimately mortality if an unhealthy heart goes unchecked.

While the percent of people not seeking specialty care at 15% might seem relatively small, these specialists include cardiologists and oncologists, among others. As heart disease has been the No. 1 killer of Americans year-upon-year—until 2020 when COVID-19 emerged as the top cause of death in the U.S.—delayed heart care can result in cardiac emergencies, morbidity and ultimately mortality if an unhealthy heart goes unchecked.

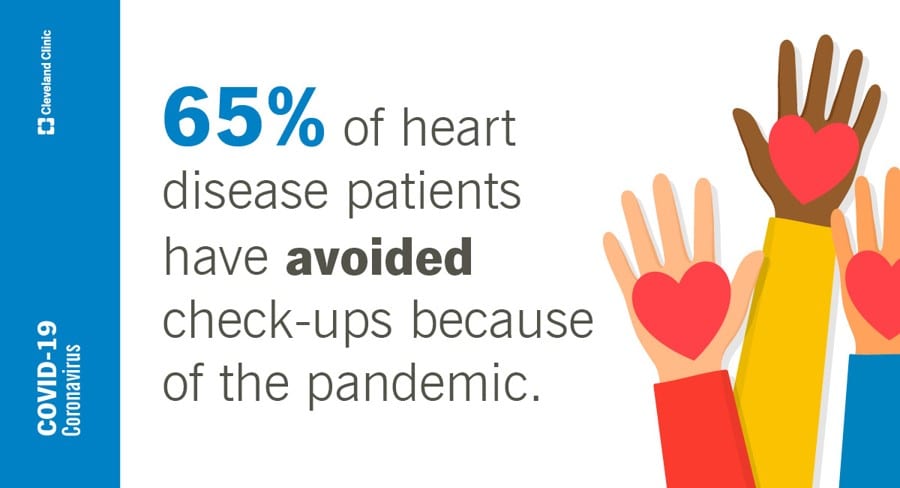

That point was of concern to the Cleveland Clinic, a major center of excellence for cardiology, which surveyed heart patients in early 2021. The survey found that half of Americans (52%) and even more heart disease patients (65%) have put off health screenings or check-ups because of the pandemic.

That point was of concern to the Cleveland Clinic, a major center of excellence for cardiology, which surveyed heart patients in early 2021. The survey found that half of Americans (52%) and even more heart disease patients (65%) have put off health screenings or check-ups because of the pandemic.

The U.S. just surpassed 500,000 deaths due to COVID-19 in February 2021. While we can expect more Americans dying because to the coronavirus in 2021, we must also prepare for other deaths due to the avoidance of care because to the pandemic.

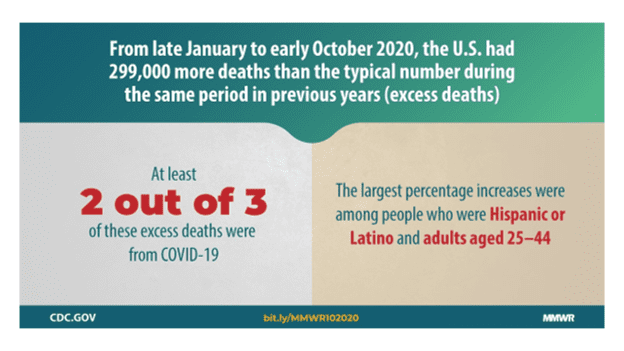

This phenomenon is known as excess mortality in the parlance of actuaries and economists.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) looked into excess deaths from the beginning of COVID-19 in January 2020 to early October 2020. The CDC calculated about 299,028 more deaths than during a “typical” year. Two in three of these were due to COVID-19.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) looked into excess deaths from the beginning of COVID-19 in January 2020 to early October 2020. The CDC calculated about 299,028 more deaths than during a “typical” year. Two in three of these were due to COVID-19.

What of the additional 100,000 lives lost “in excess” were expected? A JAMA research letter looked into that question, confirming that about one-third of excess mortality was not attributable to the coronavirus.

There are several sobering forecasts from different medical special associations and patient advocacy organizations highlighting potential scenarios for heart disease, cancer, and dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, among other conditions where patient care was disrupted by the public health crisis.

To reverse this upward trend of excess deaths will require healthcare providers and payers to bring patients into needed care workflows that are accessible, safe and without cost as a barrier to accessing the treatment. That is a tall order for the U.S. healthcare system that is largely financed on the basis of volume and not value-based payment.

It’s incumbent on healthcare providers and “payviders” who can engage in community-level engagement to do so, to identify patients who are avoiding necessary care and provide safe navigation to getting that care. This innovation could involve a portfolio of different services that can enable a particular patient with her own constellation of challenges preventing her from seeking care: whether financial, logistical (think: safe transportation), payment/cost, or educating on hygiene protocols that the health system has undertaken to keep healthcare services safe to consume.

It’s incumbent on healthcare providers and “payviders” who can engage in community-level engagement to do so, to identify patients who are avoiding necessary care and provide safe navigation to getting that care. This innovation could involve a portfolio of different services that can enable a particular patient with her own constellation of challenges preventing her from seeking care: whether financial, logistical (think: safe transportation), payment/cost, or educating on hygiene protocols that the health system has undertaken to keep healthcare services safe to consume.

Patients’ everyday lives depend upon providers getting patients back to healthcare.

Want to hear more? Check out Jane Sarasohn-Kahn’s take on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare consumers.

About The Author: Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Through the lens of a health economist, Jane defines health broadly, working with organizations at the intersection of consumers, technology, health and healthcare. For over two decades, Jane has advised every industry that touches health including providers, payers, technology, pharmaceutical and life science, consumer goods, food, foundations and public sector.

More posts by Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA